Well. It’s certainly been a minute. To all 20 of you who have been subscribed for the past two years (and probably forgot, let’s be honest), thanks! Hopefully you’ll appreciate this life update. To anyone new I share this with, welcome! I hope to write about my coding escapades here. Hopefully I can entertain, or perhaps even teach you a thing or two about your tech. First, some updates.

Where Has the Time Gone

It has been a whopping 975 days since my last blog post. In that time, I have shipped multiple projects to audiences of thousands, designed a computer (sort of) from scratch, built my own neural networks (a couple times), published a game, and won a hackathon for $2,000. I’m going to do a “brief” (I’ll try, I promise) overview of my major projects for the past two years (many of which were years in the making themselves). Officially, this post is about The Politicosmos, our hackathon project. I’ll get to that below.

Also, website update! There’s now an (automatically generated, of course) outline, either pinned on the left if you’re on desktop, or above this if you’re on mobile. If you ever get bored, feel free to skip around!

Scorecard

The AISD (my high school district) grade portal, Frontline, is… functional. At best. So Adrian Casares and I (along with a team that slowly broke apart) set out to improve it. It was a great idea. We called it, very creatively, Frontline+. Oops wait nope, thats a dog food brand. As we learned through a cease and desist. Ok then… how about Scorecard. Perfect! We set out to achieve the first step: figure out how to get user’s data without storing their information or login in any way. We knew there’s no way they would (or reason they should) trust us, and we didn’t want to violate FERPA. So we got to work.

…and failed miserably. Our goal was to make a website where we give you a sign-in page, and you put in your Frontline credentials. Then, in your browser while you’re sitting there, it goes and pretends to be you to Frontline and gets your grade data. The key here is that we wanted it to all happen on the client. Issue is, there’s this funny little thing called CORS.

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing restrictions are what prevent me from making a Chas3.com website that authenticates to Chase.com with your session cookie and stealing all your data. Great! It also means we can’t quite do what we’re setting out to do; for obvious reasons, unfortunately. The project gets put on hold for a few months

Suddenly… eureka! We’ll make a Chrome extension instead. These enjoy a few more privileges and can make requests to any website. We get back to work, and build out a website with features for testing how assignments affect your grade, customizing the name and color, and generally making it nicer to look at than a big grid. After a few months, we’re ready to publish.

There’s only one problem. The district won’t whitelist our extension… and a third of the school uses school Chromebooks. You might think that this is where we throw in the towel, say “we tried.” Not so.

The district may not like it, but the students who could use it sure did. So we did the only thing we could: we spent months upon months learning how to make a mobile app and rebuilding from the ground up.

To name a few things I had to learn for this: React Native, Expo, Swift, Kotlin, AWS, PostgreSQL, and DNS. Whew. Well, it was well worth it, because the new app was everything the website was and more. It looked better, had more customization features, and we even added notifications for new grades. The time came to publish it. We went to the school, and presented what we had; seeking if not their blessing, at least their assurance that we wouldn’t be prosecuted for advertising in school. Their response? “Nice app! Can’t advertise in school.” That meant not Canvas notifications, no posters, no morning announcements—none of the usual means of information dissemination.

Well, we weren’t about to give up now. We advertise on social media, word of mouth, everything we can do. It works. The user count climbs from 200 to 300 to 400 in the opening weeks. People are using it. A few weeks in, a friend says he saw someone using it in his church. You may think that’s the end of the story, but hardly. As part of the app, we had a feedback system in place that I personally monitored.

Aside from the dozens of bugs I fixed, people soon started requesting new features. More icons. Reordering classes. A homescreen widget. Club listings. As I churned my way through the easier requests, I felt an immense pride; we had created not just a tool, but a forum with which to bring students’ wishes to life. I poured hours into learning native code (Swift, Kotlin) to make a homescreen widget. Within days of pushing it, the metrics told me hundreds of students were using it. Eventually we realized it was time for v2.

Up to this point, we hadn’t needed our own data, or a server even; it all happened locally. But now people wanted clubs. So, I learned AWS and SQL, we created a backend, and an API. We got clubs to sign up on club fair day, passing out flyers. We added tools for clubs to consolidate their email/text lists in one place, and send out notifications. A list to see what clubs existed, their descriptions, and where/when they meet. A few months later, it was ready.

We ultimately got 50+ clubs to sign up, with hundreds of combined members on Scorecard. We amassed some 4,000 users across the district, and to this day have over a thousand monthly active users. It is a testament to what dedication, ambition, and teamwork can accomplish. And, I hope, a precursor of what’s to come. This project was quite the journey, but it resulted in the magnum opus of my high school career, and I couldn’t be more proud. But at the same time as the latter half of that, far more was going on…

Voidwatch

“LOOK ALIVE, MAGGOT. My name is General Forrest Benedict. Welcome to Voidwatch Academy,” are the words that greet you when opening up the tutorial to Voidwatch, a game I’ve developed with Aedan Ramos and Grant Bell. I’ll keep the story of this one a big shorter, but boy has it been a journey. For context, Aedan is a big game nerd. Having aspirations for a collegiate career in game design (which he achieved), he convinced Grant and I to join with him in establishing the LASA Game Development Club. While the club didn’t last long, the game idea that came out of it did.

Voidwatch is a fast-paced top-down space-shooter roguelike bullet hell. Got all that? Frankly, it’s a bit difficult to explain, so here’s the trailer:

Credit to Ezra Thiel for that one. Making a game certainly taught me the importance of clean code. At one point, I had to establish D.O.G.E.: the Department of Game Efficiency. That commit touched some 300+ files. It also really drove home the saying that 90% of the time is spent on 10% of the content—the polishing took forever. But I’m super proud of where we got it.

If you get the chance, definitely check it out! The demo is free and available on all platforms from Steam. I’m taking a step back from it for now, but as CTO of Dusk Blossom Games LLC., I will certainly be aiding from afar as the game progresses towards a complete state. I’m sure I’ll be writing about Voidwatch again. But of course, that’s still not all I was working on during that time period…

BRANCH-32 (LALU on steroids)

A fully fledged app and videogame weren’t enough, apparently. Junior year, I took a course called Digital Electronics. It was absolutely amazing, and my first foray into computer architecture. Huge, huge, huge shoutout to Mr. Mueller, my teacher. Well, as you may or may not know, computers are made of circuits. And those circuits are made up of a whole bunch of logical gates (ANDs, ORs, XORs, etc.) that work with the bits to make cool things happen.

Well, in that class, we make a basic 8-bit microprocessor. We called it LALU: LASA Arithmetic Logic Unit. Sort of like a really pared-down version of a single core of the CPU in whatever device you’re on right now. If you’re unaware, a core is essentially a duplicate copy of the processor (not accounting for virtual cores) to do, well, processing in parallel.

While processors really deserve their own incredibly long blog post, here’s the rundown. If you want to know more, please reach out! It really is a fascinating topic. They’ve got some number of registers, which are persistent storage of some number. Each register can store some number of bits; 8-bit processor = 8 bits. Now, when you’re programming processor, you’re giving it a sequence of instructions about what to do with those registers; put values in them, add them together, load from memory, etc.

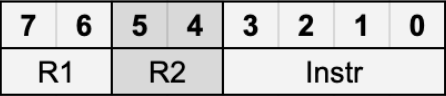

The way we encode those instructions is another series of bits. Instructions themselves have to be able to be stored in memory, registers, etc. Which means for an 8-bit processor, instructions get 8 bits to work with. Here’s an example of one way to use those 8 bits to encode anything you could possibly want to do:

The first two bits tell the processor the first register you’re using. The second two represent the second register, and the final four are used in specifying an instruction. Now, with some quick math, we can see that this allows us to specify registers R0→R3, and 16 possible instruction IDs. You can see how the number of bits of the processor dictates everything about it; size of registers, how many registers you can have, how many instructions you can fit, etc. 8 isn’t a whole lot, but it was enough for us to get a feel for how a processor works in the class.

Throughout the course, we filled out 14 of those instructions, writing them all in their basic component logic gates. The final assignment for the project? Create those last two. Well, I texted my friend Grant Bell (yes, the same one as above), and he got back to me with two dozen ideas. I thought on it for a bit, but just didn’t want to limit myself. There was only one thing to do: upgrade to 16-bit.

Now, it’s not quite so simple as changing a number. That means adding more registers, re-speccing what instructions look like, and changing literally every single wire to be of bigger logical width. I just decided to start from scratch. However, everything’s easier the second time, and I had the entire processor rebuilt (with all the new instructions) by the time the assignment was due.

Then Mr. Mueller introduced FPGAs. Field Programmable Gate Arrays are circuit boards made up of a bunch of logic blocks, which can each be programmed to act as a certain gate. Essentially, they allow you to run your designed circuit on a physical board without having to pay hundreds to manufacture a prototype. As soon as I learned of them, I knew I had to get LALU to run physically.

During finals week, I spent upwards of 7 hours in Mr. Mueller’s room some days (don’t worry; most of my classes were APs without finals). Slowly, I figured out the secrets. One of the big sticking points is that the FPGA is programmed using an HDL (Hardware Description Language). It’s a very, very low-level language that operates one step above logic gates. We were working in a visual logic gate editor called Logisim.

Fortunately, someone else had this problem, and Logisim supports exporting to Verilog. We’re on. Over the next several weeks, I do it; I get LALU to run on an FPGA. And then I have a thought. FPGAs are more than just circuit boards. They have ports. Specifically, the DE1-SoC FPGA at hand has a VGA and PS/2 port. If you weren’t alive some two decades ago when these were in use, VGA is for a display, and PS/2 can connect a keyboard and mouse. Perhaps you see the vision.

Here’s a quick aside on how an HID (human interface device) like a keyboard or monitor talks to your computer. They all use some sort of port: nowadays, USB. Any port/cable has certain pins on either wide with which to transfer data. Each device defines how it wants to send and receive data along those pins. You’ve probably heard of programs called drivers. Those programs know those device specs, and are the interface that let other programs (such as the OS) interact with the device without needing to know the details of the hardware.

In our case, we don’t exactly have an OS yet. So for a program to interface with these devices, we need to have instructions that can do that. We have two options for this. The first is to make instructions that set the pins directly and write a driver program in assembly. The issue with this is that our instructions can only run so fast, based on the hardware. At that point, we were operating at about 2 kHz - 2 thousand instructions per second. Unfortunately, that’s far too slow to write all 18,432,000 RGB pixels per second for a 60 Hz 640x480 VGA monitor.

Fortunately, the hardware itself can run significantly faster than our poorly optimized processor. We needed to implement a driver in hardware. This essentially means creating a little mini-processor that sits between the port and the CPU which takes in logical data (say, a letter to display) and operates on a 50 MHz clock to get that data written to the port. This took scouring the internet for decades-old documentation, and a lot of being stuck. But eventually, it worked.

Keyboard, 16-bit processor, and monitor, working in perfect harmony to send letters to the screen. It was amazing. Thrilling. And really, really slow. There was noticable delay between typing and seeing the letter, not to mention you could spam letters and get it stuck in a queue for minutes. The issue was, we were still working in Logisim rather than pure Verilog, and just couldn’t achieve the level of optimization required. It wasn’t an easy decision, but it was once again time for an upgrade. Enter BRANCH-32.

Towards the end of winter break just this past year, we got together with yet another friend, Pedro Couto, to design. We had learned a lot over the past two iterations, and we were going to do it right this time. While we were at it, we decided to shoot big. We were feeling the constraint of 16-bits, and wanted more. A mere two decades after the world deprecated them, we set out to reinvent the 32-bit computer.

Well, I won’t belabor the process, but we sat down for several hours and wrote it all out. We designed our own instruction set, made design decisions based on the hardware limitations and abilities available to us, and even invented some novel instructions. We had the roadmap: it was time to execute. Over the next two months, I rebuilt the entire processor from the ground-up in Verilog. It certainly didn’t all go to plan, and the spec had to be changed. We kept expanding scope, and eventually made a full branch-predictor (while the specifics are unnecessary, it had long been a stretch goal of the project).

I set up a toolchain, learned Verilog, and debugged so, so, so many issues. I got adept at thinking in clock cycles, and watching waveforms closely to pin-point which instruction was malfunctioning, which wire was (digitally) disconnected. It was painful, excruciating, tedious, exciting, riveting, and something entirely our own. It was a slow process, with many weeks spent accomplishing seemingly nothing. Until it worked.

BRANCH-32 had finally achieved, then surged past the capabilities of LALU 2.0. A full 32 registers, call-stack with built in securities, bit addressing, automatic paging for a gigabyte of RAM (a lot, to us), and I/O support. Once again, I typed out that infamous statement “Hello, world!” on my keyboard—and this time the letters appeared on the monitor near instantly.

While I highlighted my efforts, Grant put in hours upon hours (and much of his sanity, I fear) info writing our own compilation chain and langauge. We slowly began to write high level programs and compile them into our own custom assembly. While we admittedly had many tools available to us that those original engineers did not, we had successfully re-invented the 32-bit computer.

The project is not done. One day, I will see an OS running on BRANCH-32. In the next two semesters, I will be taking computer architecture and operating systems, and I am more than excited to revisit this project. But somehow, there’s more…

M.A.N.T.I.S.

Malcolmb’s Adaptive Network Threat Identification System. This was my independent study project in the fall of my senior year—before BRANCH-32 took over my spring. To give some context, I have become more and more interested in cybersecurity as a field. Even if not as a primary field, it permeates every other aspect of computer science. For 6 years, I competed in the CyberPatriot youth national cybersecurity competition, put on by the Air Force Association. We compete in teams of five to secure computers that are full of vulnerabilities, and get points. We’ve consistently made it to the highest tier of Semifinals, but never dreamed of making Nationals.

Two major things happened for my cybersecurity career Junior year. First, I participated in a CTF-style competition called CyberStart. CTF stands for Capture the Flag, and it encompasses a broad range of short challenges in which you accomplish a task (hack a thing, break a cipher, etc.) to get a “flag” to turn in for points. Out of some 250+ challenges of progressive difficulty, I completed all but 6. This placed me in the top 500 contestants nationwide, earning me a scholarship to a virtual cybersecurity course at the SANS institute, and subsequent GIAC certification.

In fact, it was two courses+certifications, but the second was significantly more in-depth. I took this course spring of my Junior year, and it has been foundational to my understanding of organizational cybersecurity. The other thing that happened Junior year was that my CyberPatriot team set out to be one of the top 12 teams in the nation to make it to Nationals. And we did it. Having never before even considered it a possibility, we prepared harder than ever. I studied harder for Semifinals than any of my midterms. And somehow, we made it.

Nationals was an amazing experience (they flew us out to Washington, D.C.) and we placed 7th, but that’s not the point of this section. With my newfound cyber experience, I had some new ideas. Specifically, using neural networks to detect anomalies in network traffic. Neural networks can be trained to predict events in a time-series; it’s easy enough to compare a prediction to reality, and flag anomalies. In theory.

This was also my excuse to learn more about neural networks. I’m not going to get too far into the technical details because this post is already so long, but as always, feel free to reach out. I researched papers and types of neural network models and eventually settled on an LSTM: long-short term memory network. I built it in C++ from scratch, and trained it locally. I taught it the Fibonacci numbers, and it discovered the golden ratio. Overall a huge success, and a ton of fun to research, learn, and create. It also gave me a much deeper understanding of what’s really going on inside AI. On to my final major project.

EditPlayerData (BTD6)

This one is far less impressive technically than everything above. However, any project that garners upwards of 80,000 users deserves some attention. Many games have some save file stored locally that can be edited if the need arises. Say, you lose some data, want to clone a profile, or just unlock content for modded play.

Bloons Tower Defense 6 does not have any such capabilities. This is partly because it has some multiplayer aspects, but save editing doesn’t interfere with those. So, I set out to make the solution. It required me to actually do some UI design of my own and not just make a tool for myself but a product that others can use. And to keep up with and fix bugs, or add features as the game expanded. I added ways to edit and export just about all the data I could think of, and published it on Nexus mods; a mod distribution platform. I didn’t do any advertising, beyond putting as many keywords in the title as possible. And it worked.

This isn’t necessarily one of the projects I highlight the most, but it is amazing proof that computer science can be used to make tools to benefit thousands. No marketing, deception, or sale of soul required.

That’s all for my projects of the past couple years. Hopefully you enjoyed if you read it all! It’s been an amazing journey, and I’m so, so excited for what’s to come. Many of those topics deserve their own full blog post, but unfortunately, I will likely never find the time. I hope to keep this updated with my future projects though! On that note, I did recently win $2,000 at a hackathon…

The Politicosmos

Well, “I” is a bit of a stretch. I worked with Arhant Choudhary, Miles Fritzmather, and Rachit Kakkar. We didn’t form a team until a week before the hackathon, but by some serendipity, we didn’t have to go with random teammates. One of the biggest immediate challenges was coming up with an idea we were all excited about. Now, for some time, I’ve been thinking about some possible tech ideas in the political space. While I’m not going to get into the breadth of those ideas (though stay tuned…), this is along those lines.

Here’s the rundown: a 3D rendering of congressional bills that you can fly around and explore. Click on one, and it will reveal a popup full of interesting information. Current state, what the projected steps to become a law are, who sponsored it, who’s voted for it (if votes have happened), etc. Furthermore, each bill is colored in 3D space according to its political leaning, and sized by relevancy. More on those heuristics below. While I brought the political side of it, Arhant was the one who both wanted to explore a 3D website like this, as well as made it fit the theme: celestial!

Data Scraping

The first step of this project is getting data. While we weren’t entirely sure the full details of what we were going to do with the data, we sure needed a lot of it. Thankfully, The Library of Congress actually has a really well-made and documented api at https://congress.api. Here’s all the data we got:

-

Bills

- chamber + number

- title

- sponsors

- committees

- cosponsors

- actions

- most recent House vote

- most recent Senate vote

-

Representatitves

- name

- state

- party

-

Votes

- yeas

- nays

- presents

- no votes

All of that is directly stored in the API. However, there are some things that we have to do to parse it. Specifically, when getting what actions have happened on bills. This gave me the most trouble, as there’s no well-defined list of actions. It’s an amalgamation of archaic IDs from several data sources and not easily computer-processable. In fact, there’s IDs for things that have happened but a few times in history that I had to account for. Ever heard of the line-item veto? It’s pretty funny, and gave me some edge cases to deal with.

Post Processing

Once that was scraped, it got put into an SQL server for ease of access. We then did some post-processing on it using Python. Specifically, we used some free AI credits we got for the hackathon to run it through Gemini to create English-language summaries of them and generate some categories from a pre-set list. That’s all an LLM. But here’s the cool part. When LLMs take in your input, they have to somehow turn words into vectors. They do this through an algorithm called word2vec, which uses a neural network to do semantic analysis. Well, there’s a similar algorithm called doc2vec that does the whole thing but with entire documents. We used that on bills.

Just running the neural net locally, we passed all 8,000 bills from the current Congress through this algorithm. That gave us a ~8k ✕ 8k matrix, where each cell gives a “similarity score” for those two documents.

From there, we use an algorithm called T-SNE dimensionality reduction. The basic concept is to take all of those vectors in 8k-dimensional space and put them in 3-dimensional space, while still maintaining some concept of “shape,” as we’re going to be visualizing them. In this case, it produces roughly a sphere.

Now, we do that same process again, but on the ten or so category titles. Now, each bill’s position is offset by its category’s position. This means that we have distinct clusters based on bill category, and then within those clusters, bills are grouped together by similarity. Finally, we whipped up a NextJS website with 3JS as our 3D rendering framework.

Result

That’s about it for the tech! It was an insane process to code for literally 24 hours straight. The hours of 5-8 were a bit brutal, but I don’t regret a thing. While we didn’t exactly make the prettiest, or most maintainable, code, and I wasn’t entirely sure it would all come together, by the end we had something pretty cool. Where we would go next is add more ways to filter the bills in order to give you more of a path to explore, as it can be a lot to see at once. That said, we did add a switch that makes it only show the bills that became laws. It’s stunning to see 8,000 stars drop to 20-something.

After a short break to pet some dogs, eat some food, and feel (slightly) more alive, it was judging time. We didn’t do any rehearsal and scarcely sketched out what we were going to say. We were all proud of what we had made and for surviving the night, but frankly, we weren’t really expecting to win much if anything. We didn’t go for any of the tracks, and we felt the flaws (and bugs) in our program keenly. But the first judge came around, and we built our pitch on the fly. We each took a section, with me leading the intro and conclusion. We spoke to our technical depth, and I did my best to sell them on the social importance. The judges seemed to like us, but it was hard to tell.

After some two hours of judging, we were exhausted. The judging period technically wasn’t over, but we all headed out 10 minutes early after not getting any action for a good bit. None of us had the energy to stay for the closing ceremony; after all, what are the odds we win anything. Right?

Well, I wake up after sleeping for 16.5 hours to a dozen texts. Turns out, we won Best Novice out of some ~100 novice teams (of ~200 total). The total prize is $2,000, amounting to $500 per person. While I’m not quite sure $20/hr is worth the sleep deprivation, the experience, and resultant product, certainly were. Not to mention the validation that we actually did make something pretty cool. If you want to check it out, here’s the link while it’s up. No guarantees for how long it will be, so sorry if it’s dead! WASD to move, click to rotate, get close to stars to click on them! (and yes, it does just take like 30s to load. I don’t wanna hear it.)

Closing

Thanks for reading! I know this was a long one, but boy has it been a while. If you have any questions or comments about any of the above, reach out! Always happy to chat.

If you enjoyed the storytelling or want to keep learning about our tech alongside me, put in your email below! You’ll get a notification the next time I write something.

Either way, that’s all I’ve got for now. It’s been a wild ride, and there is so, so much more to come. I’ve only just started on my biggest and most ambitious project yet, after all… But for now, see you next time!